Inkbrook Design: The Portfolio of Mackenzie Cameron

Resume | Portfolio | About Me |

Eistein: His Amazing Life and Incomparable Science was Artana's first foray into a family-friendly experience that would appeal to distributors as well as our core kickstarter customer base.

The result was a geometric game that mirrored Einstein's penchant for visual learning. We more than doubled our Kickstarter goal, and exceeded order expectations from our distribution partner.

My role as Developer was to help the in-house Designer iterate the prototype and provide insights through playtesting. I also worked with our visual designers and marketing lead to ensure standards and meet deadlines.

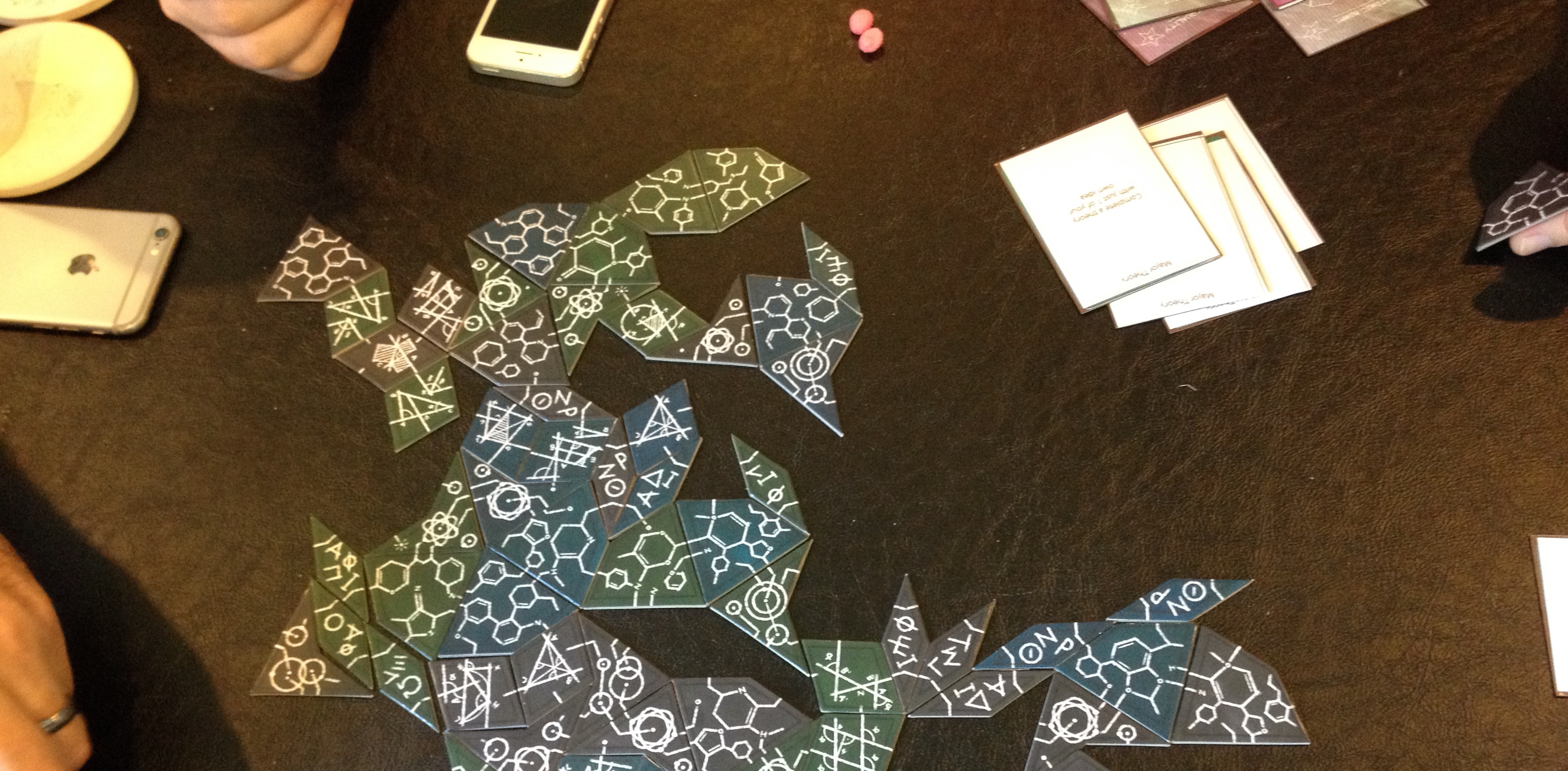

The first several designs ranged from worker placement to route building. We quickly built, tested, and iterated prototypes as part of our internal brainstorming.

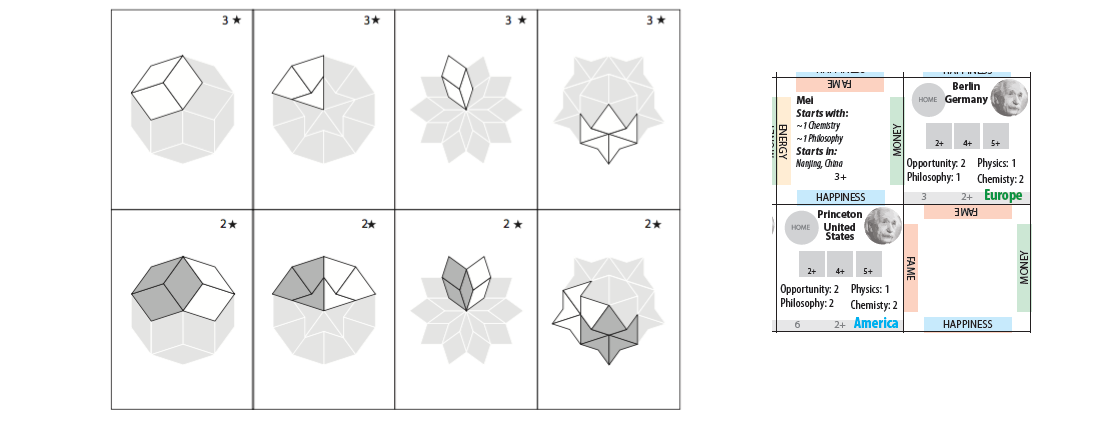

A core concept emerged: players would use color-coded Penrose tiles to build a central shape, and score points for creating specific shape-combinations shown on cards.

Once we had a good idea that the game could become viable, we set out some core principles. The designer and myself agreed upon specific goals that would guide the progression of the design.

Deciding on the core gameplay around penrose tiles was the transition from broad concepting to slightly more narrow iterating.

Constructing multi-tile shapes was fun, but what combination of pieces would make it a balanced game?

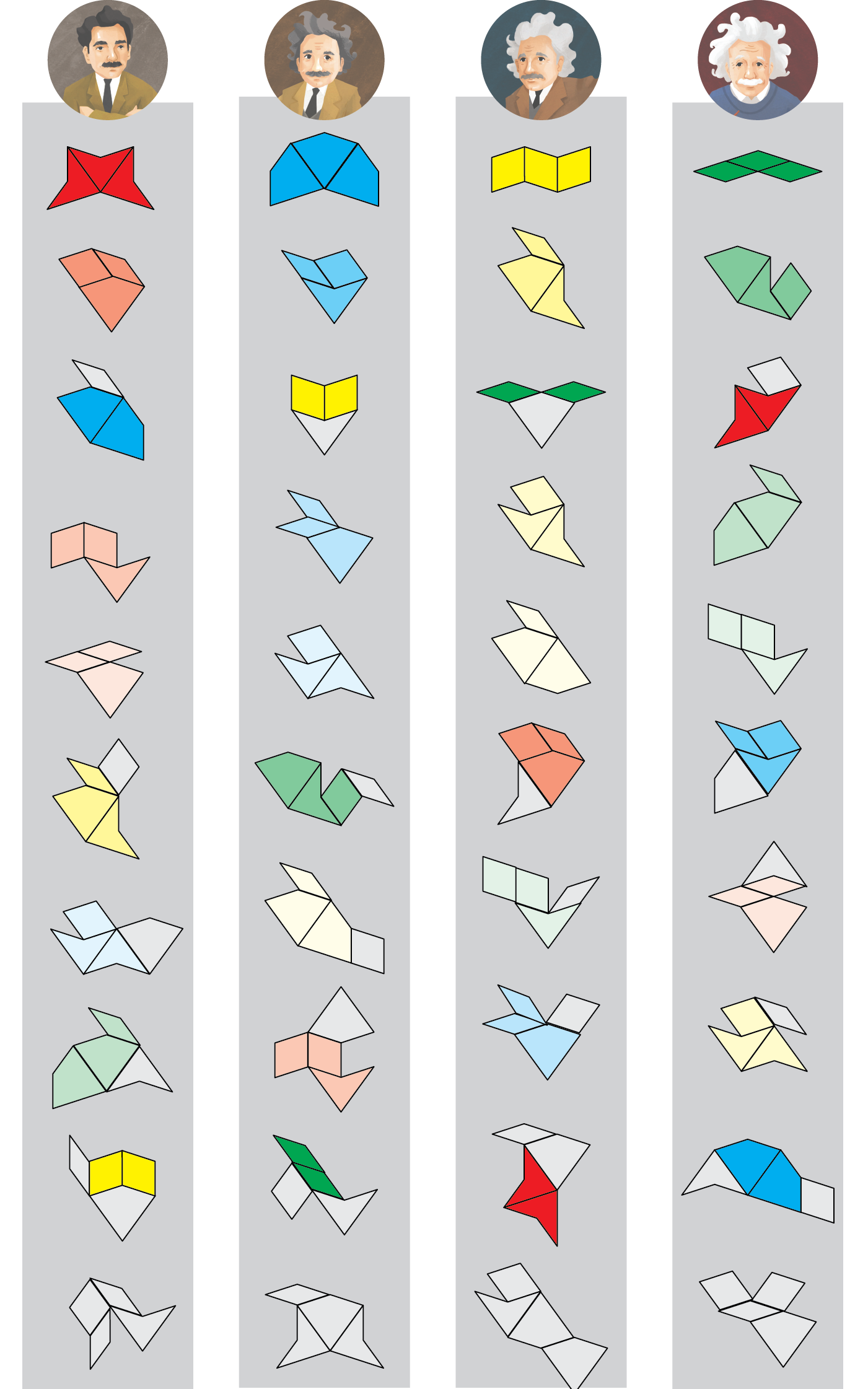

Each player has a personal deck of cards with tile combinations they are attempting to build on a shared board. Each deck needs a unique set of tile combinations, but also requires an equal distribution of 4 different tile shapes.

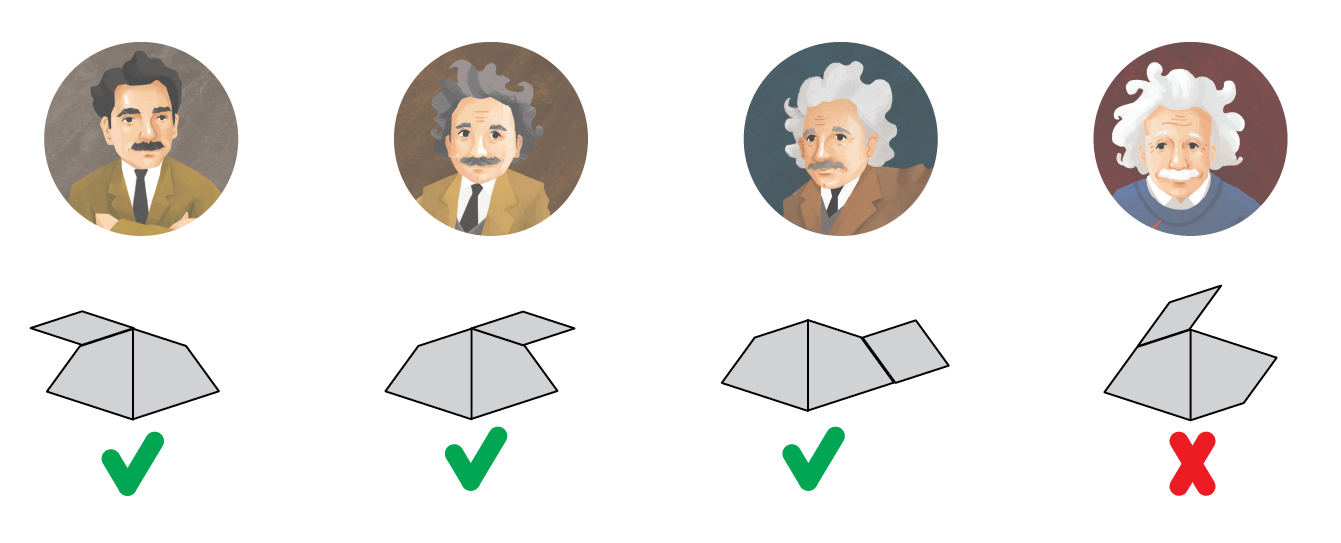

Through early playtesting, I also realized that orientation of the shape really matters. In the example below, if there are two large diamonds with tips together 3 players could score by placing 1 tile, but the fourth player would not be able to score because his goal requires a large diamond to be inverted.

My personal triumph of this project was understanding the relationship between these shapes and gameplay. I built a number of visualizations to help the team wrap their head around these complex permutations.

By understanding these complex geometric relationships, we were able to evenly distribute these positive and negative interactions between players to create unique gameplay opportunities. This concept carried us into our testing phase to rigously validate what would and would not work as an actual game.

Artana has access to playtesters who are part of a dedicated mailing list. I built a very lightweight "print and play" prototype kit in Adobe Illustrator, with instructions on how to assemble and play it.

20 active individuals played and provided feedback over multiple iterations. We collected both qualitiative and quantitative data through Google Forms. This helped us better balance the mechanics of the game and start to move from a "viable" game to one that achieved our core principles.

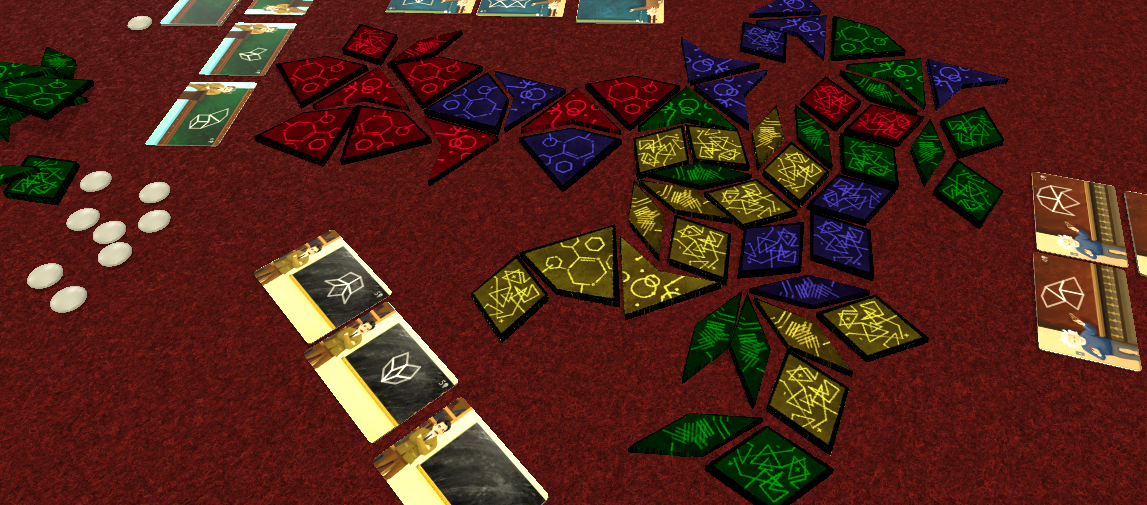

In addition to our external testers, we found great success using a program called "Tabletop Simulator". Many of our team members telecommuted, and I was able to build a testable prototype that we could play over an internet connection. This allowed our team to play the game together and discuss the incoming user feedback with much greater frequency.

We brought Einstein to Origins, GenCon, Pax East, and BGG Con, and demoed the prototype over a hundred times.

A big part of playing a board game is understanding the rules, by explaining it repeatedly to players, we were able to note important ways players learned and understood the game.

These in-person playtests were incredibly valuable in getting a direct view into how our players engaged with the game.

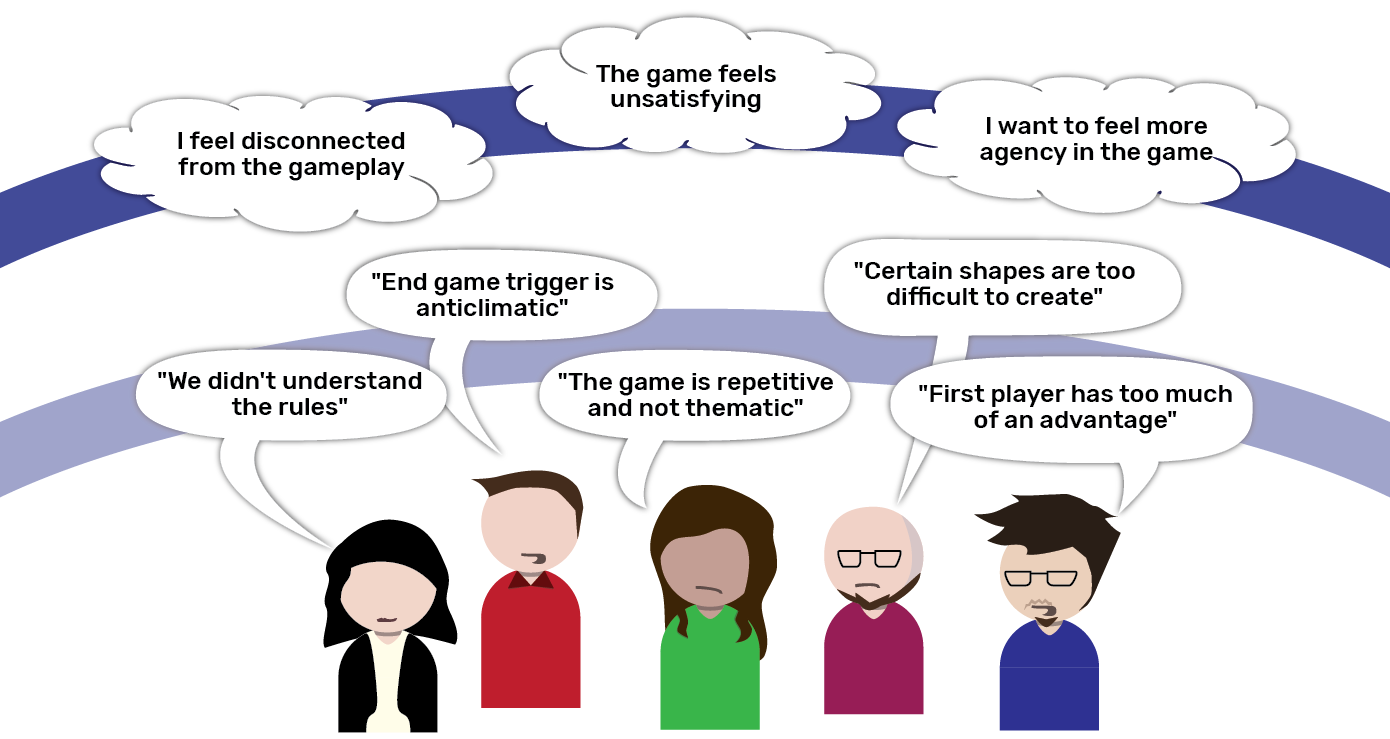

Armed with hundreds of pieces of feedback, we dug through the data to better understand themes and pain points encountered by players.

While the majority of the feedback was positive, we surfaced 5 major trends worth considering.

By digging into these trends we were able ascertain root cause of some pain points and address them.

Immersion is important in gameplay. Not only does it drive engagement, but it can reinforce learning and cognitive performance.

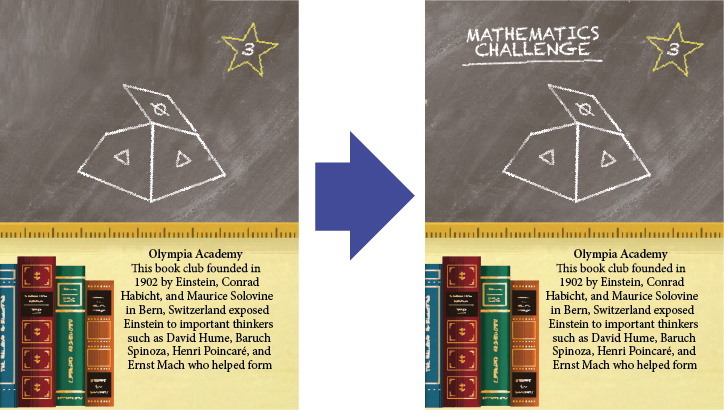

Originally, the cards had abstract suits like "logic" and "history". We introduced the concept that each card represented a specific achievement from Einstein's life. Player reported better engagement, when completing cards labeled "Theory of Relativity" or "Patent Office Job", because it gave them more concrete milestones.

While we strove to make a childrens game, we actually uncovered that many players, including young players, felt the game was too "one note". In some cases, what we had thought was "streamlined" was actually "monotonous".

Through many iterations, we introduced a second set of shared cards that allowed players to drive towards some different goals. An important element to this was that while the goals were visible, they were optional. The mechanic wouldn't disrupt young players or new players, but could provide added variety at the moment they start to get comfortbale with the game.

"Starting player has too much of an advantage" was the most common piece of feedback we received. However, we kept track of victories for most of our playtests, and looking at the numbers it actually looked like the starting player lost more often.

We ran several playtests to better understand what was causing the "perception" of this advantage. While starting player got to place the first piece, later players tended to have a slight advantage because they could see more of the board. The first tile was almost a throwaway move, but players perceived it as agency. The starting player did tend to get more "actions" even if those actions were less valuable towards victory.

Players can't see the nuances of value, but they can see that it "looks" like starting player gets "more". We were able to modify some elements of turn order to design around this perception and help all players feel like they could engage more with the game.

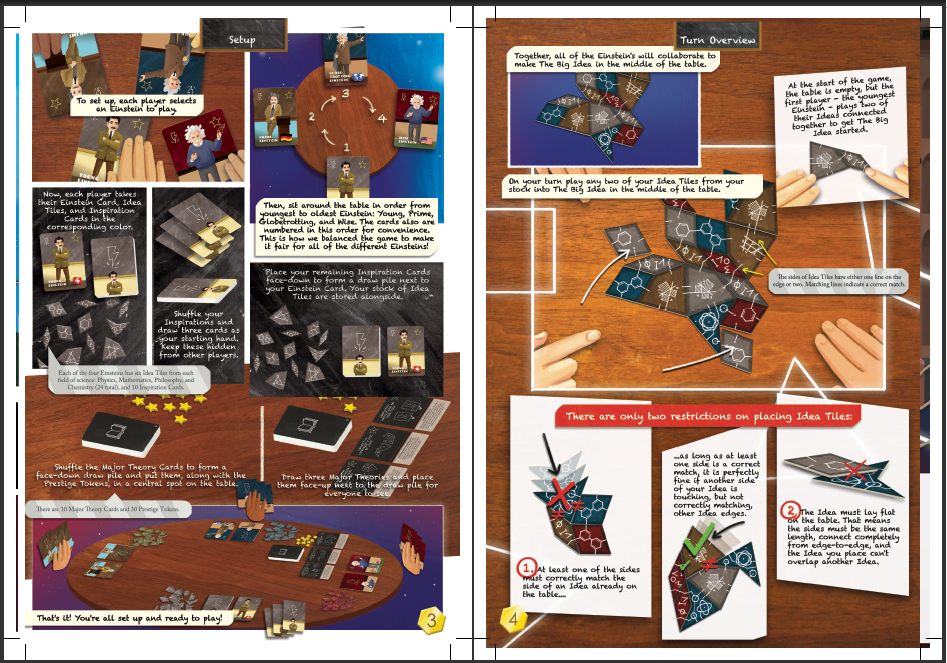

With the game feeling solid, I worked with an illustrator to layout the rulebook and all of the components to be ready for manufacture with our production partner.

Helping draft a complete rulebook and ensure all our components complied with the proper format is a story all it's own, but it was an instructional opporunity on the importance of clear communication.

We went through multiple iterations of "blind" testing, watching players teach each other the game using early drafts of the rulebook to help us conceive a booklet that was helpful and easy to use.

In the construction of this game, we built up a good community who helped spread the word and push us well beyond our Kickstarter goal. The game was well received by reviewers and I attribute much of that success to our rigourous playtesting.

We made many tweaks, and encountered many challenges, but by listening to our players and following user-centric design principles we always found a path forward.

If you'd like to learn more, you can check out our completed Kickstarter page, and I'm always happy to teach the game to interested folks, if you have a few moments.